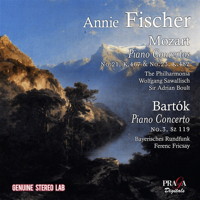

There are several recordings, both audio and video, of Fischer performing the Piano Concerto in C, K 467, by Mozart. The studio recording presented here features her with the Philharmonia Orchestra under a young Wolfgang Sawallisch. The recorded sound is good, although the piano sounds somewhat distant, as if the microphones were placed somewhere around the woodwind. It must be one of the best orchestral accompaniments to this Concerto on record: the ensemble is tight but warm, phrasing is light and graceful, and, possibly because of the placement of the microphones, the ensemble between piano and orchestra, especially the woodwind, is unusually transparent. Fischer herself plays with the characteristics familiar from her other recordings: without being overly intrusive, she shapes phrases in an entirely natural but rhetorical manner, often placing themes into a new light. Articulation and expression are always clear and precise, and her overall view of the Concerto is energetic without ever becoming excessively rhythmical. As in all her other recordings of this work, Fischer plays cadenzas by Busoni for both the first and third movements. As Mozart did not supply any himself, and no other composer has contributed a definitive set in the manner of Beethoven and the D Minor Concerto, pianists are obliged to be more experimental here. Busoni’s cadenzas are clearly stylistically complementary rather than matching, but fulfil all the expectations of what a cadenza should do, albeit with some extra combinations and perhaps more distant modulations than one would anticipate.

The inclusion of these cadenzas underlines the more general problem of concerto

cadenzas: originally intended as spontaneous contributions by the performer,

they have increasingly become predictable parts of the concerto due to the high

quality of the composer’s own cadenzas or those of other specific composers. It

is difficult to justify playing Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto and not to

include one of the two cadenzas Beethoven himself wrote for the first movement,

and so the many interesting and successful cadenzas written by others, such as

Clara Schumann, never get a hearing, not to mention the performer producing one

themselves. The few concertos that do not have an obvious choice, such as this

one, are therefore rare opportunities to be imaginative without being overly

wilful.

The Concerto in A, K 488, is presented in a recording from 1960, also with the

Philharmonia, this time under Sir Adrian Boult. Whilst the orchestral part is

not as perfectly rendered as that in K 467, it is nevertheless very successful.

The piano sound is again somewhat distant, giving the slow movement a little

less impact. Fischer plays this sweetest of Mozart’s Concertos beautifully: it

is as expressive and soulful as it could be without ever crossing the line into

sickliness, a feat not always mastered in this Concerto, even by the greatest

pianists. The slow movement in particular is moving, with genuine pianissimo

throughout, the music restrained and introvert, allowing an unspeakable sadness

to emerge without any trace of melancholia.

Annie Fischer was famous for her performances of Bartok’s Third Piano Concerto,

of which there are three released recordings to date. The version included here

is the second of the three, recorded live in Munich in 1960, with the Bavarian

Radio Symphony Orchestra under Ferenc Fricsay. It is a highly charged,

atmospheric recording, the mystical opening perfectly captured, the serenity of

the second as successful as in the similar movement in Mozart’s K 488, and last

movement fiery and exciting. It is as convincing a recording as any, not

dissimilar to the recording made by Dinu Lipatti and Paul Sacher. Overall, the

recordings included on this CD are all well suited to introduce the virtues of

Annie Fischer to those not acquainted with her playing – repeated listening can

demonstrate the simplicity and vitality she brings to the music, as well as a

sense of genuine profundity.